Uploaded 23/05/22

Annual Impact Report 2021 - 2022

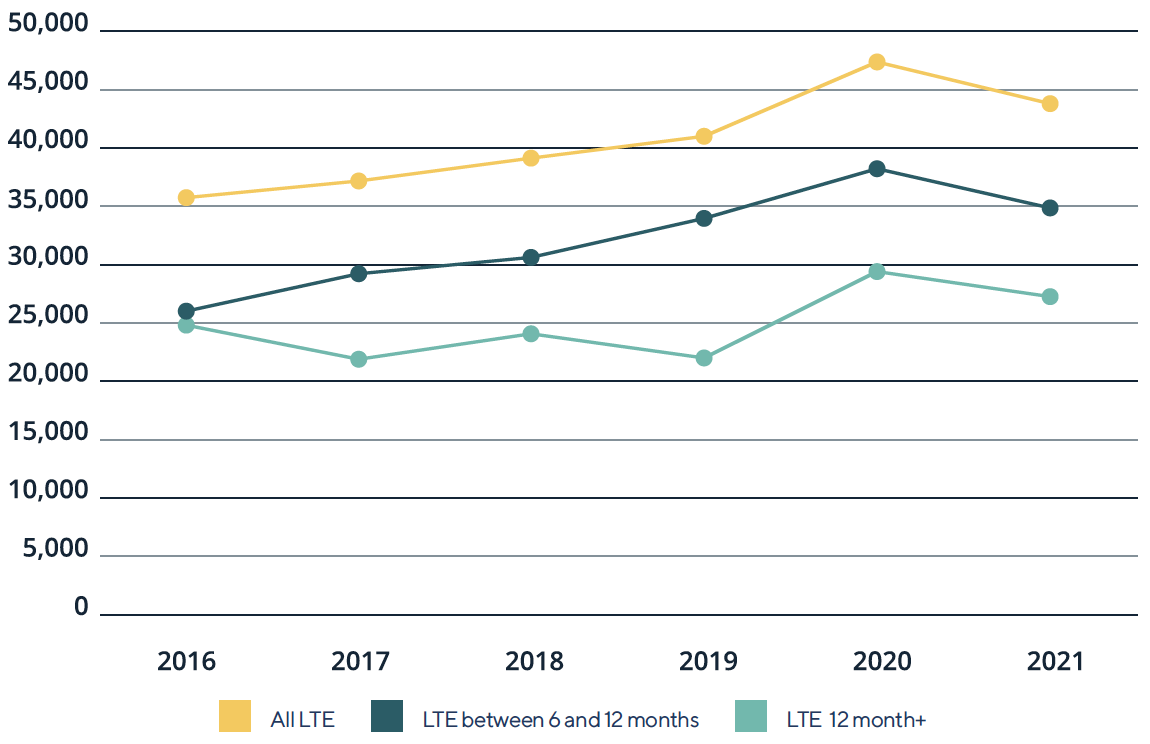

It was encouraging to see that the largest share in the fall came amongst homes that had been empty for 12 months or longer. This suggests that many of the homes that became or remained long term empty as renovation work was put on hold, rental properties stood vacant, people put off house moves and private sector landlords held back on further investment in the property market due to the pandemic, have now been returned to use.

Nonetheless, many of the 27,854 homes reported as empty for over a year are likely to have been empty for considerably longer than this, and we know that the longer a home remains empty the harder it becomes to bring it back to use. The property may suffer from deterioration, making it less aesthetically appealing to potential owners. Buyers can be put off by the overgrown gardens, flaking paint on windows and cracked roof tiles that are just the early signs of a long-term empty home. After a few years, that can be accompanied by rubbish from fly tipping, moss in drainpipes, and obvious signs of neglect inside the home for anyone who peers in through the windows.

With empty homes often acting as a magnet for wider anti-social behaviour, the broken windows and door frames together with signs of vandalism or vermin inside a house empty for several years, not only make the property less appealing to look at, they also further reduce its value and add to the costs any potential owner faces before they can return it to use.

The percentage of empty homes that have been vacant for more than a year varies considerably across the country. At one extreme, less than a third of empty homes in South Ayrshire and Edinburgh have been empty for longer than twelve months. At the other extreme, 11 local authorities reported that more than 70% of their empty homes had been empty for this length of time.

Empty homes officers and others have made inroads into reducing these numbers, but the commitment and hard work of EHOs can only take us so far to deliver lasting results that enable these homes to provide some of the homes that Scotland needs now. We are continually told that their work is hampered by the limited options currently available to local authorities where owners cannot be traced or refuse to take any action to return their homes to use.

We know that any new enforcement measures that may be proposed will need to be compatible with rights to property under the European Convention on Human Rights. However, we hope that the human rights of neighbours whose day to day life may be adversely affected by very long-term empty homes, as well as those of people who currently do not have a home of their own, are given equal consideration when the sufficiency of existing legislation is next considered.